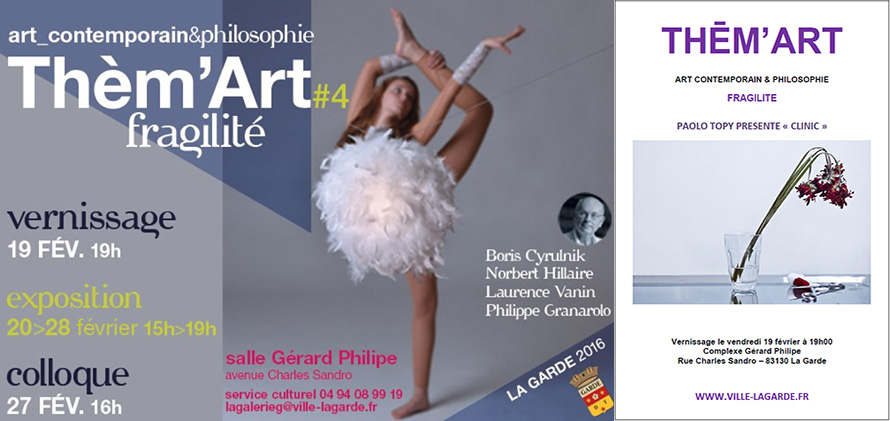

CLINIC

With reserve and sensitivity, avoiding misplaced or pointless pathos, Paolo Topy ’s “Clinic” series evokes sickness and the end of life in a hospital environment, as well as the fragility of our fates as human beings, and of our certitudes. As is his wont, using tremendous economy of means, he has managed to create a simple, easily understandable image that is rich in meaning. Disease and death are ignored, marginalized or even evacuated from our society. Thus hospitals are, paradoxically and at one and the same time, both places where the sick and dying are, at best, treated, cared for and accompanied, however awkwardly, as well as places where what we refuse to see or to admit – or in any case, what we don’t want to acknowledge, discuss or debate – is banished from our sight, perhaps too easily. Fear intertwines with embarrassment; anxiety with denial, indifference, guilt and incomprehension. To address this subject, Paolo Topy has reprised a recurrent theme in western art: the still life. Each of these pictures was taken in a deliberately aseptic, sterile and cold environment. These hospital or clinic environments are recognizable thanks to the institutional white wallpaper or the equally white, icy-looking tiles, the stiff metal and glass furnishings and the medical instruments used for caring for patients. Surprisingly or even gaudily colorful medication accentuates and winds up defining this world. The medication’s artificial colors express a clumsy attempt to bring a bit of cheer into this environment. These omnipresent materials are a pretext for a study of light, which dominates and bathes these compositions from which the artist has evacuated all human presence. The objects represented are the only things that refer to the human element, to the physical and moral suffering and the ways in which we deal with it and try, to the best of our abilities, to relieve it. The light is cold in appearance only. In fact, it expresses the need for hope: the awkward hope for a physical cure, of course; but above all, a more profound hope for serenity, calm, and above all, peace. Flowers are presented in plain water glasses. These exceedingly modest bouquets, composed of garden flowers that someone seems to have taken the trouble to go out and pick, rather than hastily grabbing something from a florist’s, have wilted too soon. They are not unlike Dutch still lives and the reflections on life, its brevity, and death they offer us, illustrating, as these images do, a verse from the book of Job: “Man blossoms like a flower, and then withers; he flees like a shadow.” While these flowers spontaneously evoke Flemish painting, for Paolo Topy, they are in fact closer to the rose that Francisco de Zurbarán delicately laid on a silver plate with a cup in a superb still life painted circa 1630 and owned by the National Gallery in London: “A Cup of Water and a Rose”. That still life expresses the Spanish artist‘s thirst for clarity and understanding, in other words, every human’s thirst for light. The glasses that Paolo Topy photographed are the same ones that the nursing staff and loved ones hold to patients’ lips, or that patients use to quench their own thirst. A thirst that is also the thirst for truth, sharing, human love and kindness; in order to better understand and to learn to accept the unacceptable, the intolerable: suffering and death. Helping someone to drink is one of the simplest and humblest acts a person can perform, and also one of the most moving; it is an act that expresses attention to another person, to life itself, even when it is has been reduced to no more than a barely audible breath. For the artist, it is indeed a light-filled act, one of compassion and truth. Sickness and death are still private and often solitary experiences, even if they are “shared” for the length of a brief visit by loved ones and friends at a loss, who, not knowing what to do, display their affection with a bouquet of flowers that will inevitably wilt, thereby evoking the finiteness of all things, of beings, and, terribly, of the ties that bind them. The tenuous warmth felt here seems to be concentrated in those few traces of veritable color that are still perceptible in the flowers. These wilting, rotting flowers are strangely beautiful. It is surely their inevitable end that grants them their uniquely deep, rich hues, that makes them so touching and so fascinating at the same time. By their modesty, they also express the distraught clumsiness of those who want their gesture to show that they, too, have been affected by what is happening. It is in these moments of finiteness, sadness and pain that patients and their friends and loved ones, as well as the nursing staff may get a glimpse of the full palette of sometimes disturbing emotions of these moments, which are difficult for those who are going through them and trying to share them. Strangely enough, and even though they probably don’t realize it, although these moments are some of the hardest in their lives, they are also some of the most beautiful. Moments when the fragility of all parties is revealed and can meet, dropping the mask of certitudes, pretense and contingencies, and making room for a possibility of comprehension for their humanity, fragility and weakness. That is when – in the sometimes tenuous, but ever-present light in these images created by the artist, within reach of our gaze and our understanding – the beauty of the experience of life, of its doubts and suffering, and even more surprisingly, of the experience of disease and death, appears.

Yves Peltier